Who Does the Church Serve When It’s in Decline?

This past week, I had the privilege of traveling to Tulsa, Oklahoma, for the Remind & Renew conference at my alma mater, Phillips Theological Seminary (PTS). For the past two years, PTS has graciously invited me to attend as part of my work with the Future Christian Podcast, where I’ve had the chance to interview some of the event’s featured speakers. It’s always a meaningful time of reflection, conversation, and learning.

On the last day of the conference, a faculty panel discussion gave attendees the opportunity to ask questions of the professors. While the questions started off lighthearted and personal, “What inspired you to get into teaching?” and “What’s your favorite class to teach?” once someone else asked a heavier question, I figured I was safe to ask my own challenging question:

“Based on sociologist Ryan Burge’s data on the decline of Mainline Protestantism, I’ve observed—like Ben Crosby—that if a church is to be a voice of justice and inclusion, it must first exist. But soon, we won’t, if we don’t turn things around. What does that mean for this institution?”

The panelists seemed unsure of how to answer, perhaps because the question pointed to a reality so urgent and difficult that it felt beyond the scope of an academic panel. But this question has stayed with me ever since.

The Decline of Mainline Protestantism

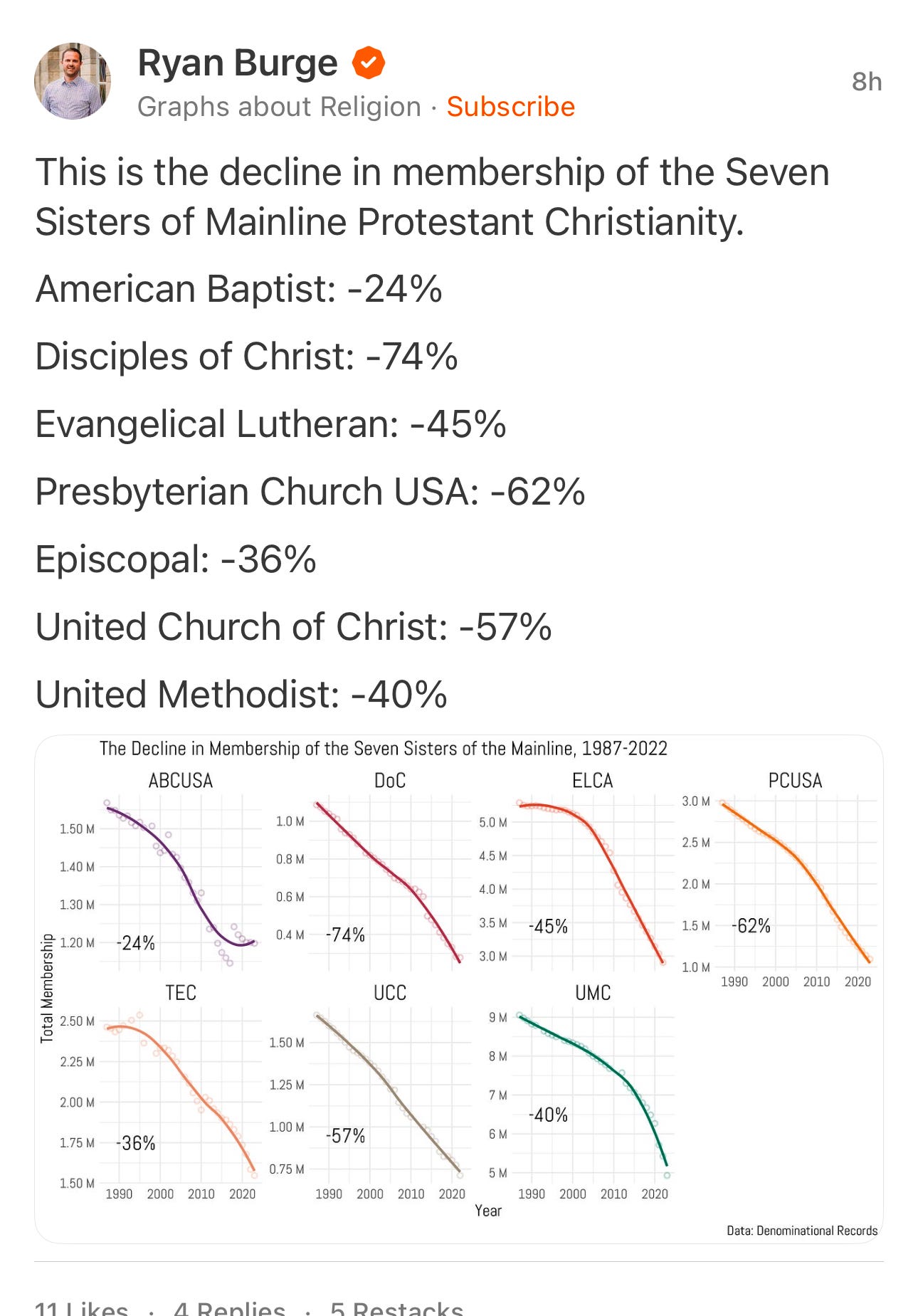

Ryan Burge’s research provides a stark visual of the ongoing decline in membership across the "Seven Sisters" of Mainline Protestant Christianity. The chart below shows the percentage decline in membership for denominations like the United Methodist Church (-40%), the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (-45%), the Presbyterian Church USA (-62%), and others over the past several decades. Particularly striking is the Disciples of Christ, which has experienced a 74% decline since 1987.

These numbers make it clear that the challenges Mainline Protestantism faces are not just anecdotal but part of a broader, measurable trend. For institutions like seminaries, denominational offices, and pension funds, this data underscores the urgency of recalibrating their missions to serve a rapidly shrinking church.

The Pension Fund’s Perspective

This dynamic isn’t just theoretical; it’s playing out across various church-related institutions. One example is the Pension Fund of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). I recall an offhand remark from a representative who openly acknowledged that the fund will almost certainly outlive the denomination itself. On a practical level, this is almost certainly true, as the Pension Fund is funded at something like 130% of its obligations. But more broadly speaking, this stark reality raises critical questions: What happens when institutions are healthier than the churches they were designed to serve? And more pointedly, are these institutions—born from the church—obligated to pivot to support the church in its time of crisis rather than simply focusing on their own future?

To its credit, the Pension Fund has launched initiatives aimed at addressing some of these concerns. For example, it has expanded its focus to include financial wellness resources for pastors and church leaders, recognizing that economic strain is a significant factor in the decline of congregations. Such efforts demonstrate a commitment to serving the church, even in its decline, rather than distancing itself from the challenges at hand.

Positive Steps at Phillips Theological Seminary

Phillips Theological Seminary has also taken significant steps to reimagine its mission in this era of church decline. While its primary focus has historically been on training clergy, PTS has expanded its vision to include broader audiences and new initiatives.

For example, PTS has launched programs in public theology and justice work, equipping leaders to engage meaningfully with societal challenges. The seminary also offers resources for lay leaders and community members, recognizing that the future of the church will require shared leadership between clergy and laity. Its hybrid and online learning models have made theological education more accessible to those who may not be able to attend traditional in-person programs.

Additionally, during the same faculty panel discussion, the idea was raised about a future rural church associate—a program focused on strengthening and supporting smaller churches and their leaders. Initiatives like these demonstrate that PTS is actively working to adapt its mission to meet the evolving needs of the church.

Reimagining Church-Related Institutions

At a broader level, seminaries, denominational offices, and other church-related organizations must grapple with how to remain relevant and effective in the face of declining membership. These institutions were originally created to serve and equip the church, but as the church itself shrinks, they risk losing sight of that purpose.

The challenge for these organizations is to ensure that they are meeting the most pressing needs of the church today, rather than defaulting to serving themselves or their own survival. Formation and leadership development must not only prepare individuals to engage in justice and advocacy but also to strengthen the communities of faith that make such work possible.

This is a call for church-related institutions to focus not just on abstract ideals but on the practical, day-to-day needs of congregations. What does it look like to equip churches for financial sustainability, effective community outreach, and deep spiritual formation in an era of decline? These are the questions that must guide the work of every church-related institution.

Refocusing on the Church

As I reflect on these institutions—the Pension Fund, Phillips Theological Seminary, and others—I am struck by a shared challenge: they were created by and for the church. Their purpose was never to exist independently or to serve their own interests but to support the body of Christ. In this moment of crisis, they must re-center their work on the church’s survival and flourishing.

This isn’t to say that serving the church means avoiding justice work or theological innovation. On the contrary, it means ensuring that the church is equipped and empowered to continue being a voice for justice, inclusion, and hope. But that voice cannot resonate if the church ceases to exist.

My core belief is this: Institutions must embrace their responsibility to the church, not just as historical artifacts but as living, breathing communities in need of support, creativity, and transformation. Only by doing so can they honor the mission they were created to fulfill.

Speaking as a priest and proud member of the Episcopal Church, the church I love, I can offer at least one critique. We are too cerebral. The article speaks a lot about justice, finance, formation and more, but where is spirituality? It would help the mainline churches to be more spiritual, more experiential in their engagement with the Divine. For instance, justice issues are critically important to Christians and churches, but if it isn’t grounded in the people having firsthand encounters with God, soul work, transcendence, then we’re just another social service agency.

One thing I shout to my denomination’s seminaries in fantasy conversations is, “Are you kidding me? The world is at this point entirely ignorant about Christianity, and you, a building full of experts on it, can’t figure out what to do with yourselves?”