Are Seminaries Still Serving the Church?

Rethinking theological education for a stronger, shared future

Recently, I had

on the podcast. We talked about her experience in Christian higher ed—especially theological education, where she served as Dean of Students at Western Seminary and journeyed alongside her husband as he pursued a Master’s degree.While we discussed the many challenges facing seminaries, explored alternative education models, and envisioned how schools might adapt to changing student demographics, a couple of Bekah’s observations have stuck with me.

1. Are Churches Devaluing Theological Education?

Bekah raised a compelling question: Are churches devaluing theological education? It’s something I’ve noticed as well—especially in non-denominational circles, where pastors are more likely to hold degrees in business or communications than MDivs. In some ways, this reflects a broader Evangelical trend of modeling church leadership on marketplace dynamics. So, it makes sense that many churches want pastors with business or media savvy.

“It’s no longer a requirement at many churches that you have to have theological training. That has been a really interesting shift to see.”

This trend is less pronounced in Mainline Protestantism, but there’s still a growing preference for candidates with outside business or nonprofit experience—even if they lack professional ministry backgrounds. I’m thinking of one ministry that chose a leader with, from what I could tell, no real church experience—even though the ministry exists to support church leaders.

To be fair, I get it. Pastoring is increasingly complex. Leading a church can resemble running a small business or nonprofit. It’s part of why I went back to school for my MBA in 2020. I recognized the shift. And yes, outside perspectives can bring needed innovation—especially in systems that feel stuck or are in decline.

But experience and theological education still matter. Sometimes in intangible, hard-to-measure ways. And we shouldn’t lose sight of that.

2. The Growing Disconnect Between Seminaries and Churches

This was another point Bekah raised that deserves attention. I’ve written about this before—though perhaps not strongly enough.

“Over the years we have seen [seminaries and churches] start to divide a little bit where it's no longer integrated as thoughtfully as it maybe once was.”

Practically speaking, I get it. As churches shrink and resources tighten, it makes sense they’d raise up leaders from within rather than wait on the latest seminary grad. And for pastors or lay leaders who are bivocational (an increasingly common reality), there’s often no bandwidth to track what’s happening at denominational seminaries.

That’s why seminaries need to meet leaders where they are—through accessible resources like the podcast idea Bekah shared—instead of assuming people will be drawn in by the traditional allure of seminary life.

“We had professors who launched a podcast to talk through the challenges seminaries and churches face together. It ended up becoming a great admissions tool, too.”

But let me say this more forcefully: seminaries must bear greater responsibility for the health of the church.

Most seminaries were founded to serve and strengthen local congregations. So I find it baffling when seminary leaders act as though the decline of the church is not their concern. We have to move past the ivory tower—or as a guest recently put it on

’ podcast, the “Hogwarts” model of theological education. Seminaries must integrate with the life of the church in meaningful ways. Bekah offered some excellent ideas on how to do this.“At Western Seminary, nearly every full-time faculty member was actively serving in a church. That was a major selling point for students.” —Bekah Buchterkirchen

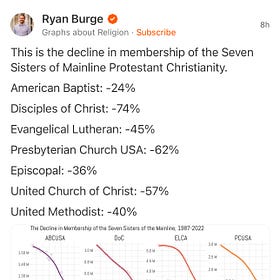

To be fair, in many Mainline contexts, the situation is reversed—not because churches are disengaging from seminaries, but because denominations themselves have watched several of their seminaries close or merge in recent years. Still, my point stands:

We’re all in this together.

The Church is stronger with robust theological education, and theological education is stronger when rooted in the Church.

As I've been reading your posts about seminaries, I've thought in terms of these basic questions.

1. Whom do seminaries exist to serve? If the top priority is serving Jesus Christ, then understanding and spreading the Gospel is foundational. Mission is determined theologically. Like disciples, seminaries are to be "not of the world."

2. How are seminaries to support being "in the world" as Christian leaders? What concepts and skills are needed in order to be effective in "Bringing Christ to the world and bringing the world to Christ?"

3. Pournelle's Iron Law of Bureaucracy describes the tendency for organizations to shift from the mission that inspired their founding to maintaining the organization for its own sake. How do seminaries avoid this themselves and teach their students to avoid this tendency in their congregations?

4. When does an emphasis on the "business" of management and sales in a congregation serve mission and when is it an example of Pournelle's Law at work, with the church "losing its saltiness" and becoming little more than an expression of either the culture as a whole or of a particular subculture?

5. How do the anxiety triggers/reactions that disciples experience affect their discernment of the answer to this question, and how can seminarians be educated to deal with emotional processes such as these?

6. What is the role of spiritual formation in seminary education?

7. What are the characteristics of a seminary that the Holy Spirit is more likely to sustain as a community and as a resource for the Church?

Within the non denominational movement there has always been a certain distrust of academia, which was more pronounced in the Charismatic Renewal branches of this movement. A person with an MBA, led by the spirit, would definitely be seen as somebody with more to offer than a seminarian. I’ve actually seen a greater trend of non denominational leaders going back to seminary as they continue their ministry in the last 20 years as opposed to prior. But simultaneously there is still a populist ethic that has grown within churches throughout the country, and the group of churches I know could be the outliers.